The First World War left a politically and economically defeated Germany. The old German Empire, practically dismantled, had given way to the Weimar Republic, but the failure of that liberal system would only cause frustration, especially after the economic crisis of 1929. The onerous war reparations and other humiliating conditions of the Treaty of Versailles fed in the population a revengeful feeling. All this, together with the roots of its military tradition and romantic nationalism according to which the State was the incarnation of the spirit of the people, as well as certain authoritarian habits of German society, constituted an excellent breeding ground for the emergence of the new totalitarianism. that were beginning to prevail in interwar Europe, like Italian fascism.

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler added racial pride to fascism to form the explosive and paranoid mixture that would galvanize an entire nation. He got the support of an army wounded in his honor; of the industrialists confronted with the unions and fearful of the Marxist ideology; of a frustrated middle class and of the proletariat “victim of the trade unions and of the political parties.” He knew how to propose to all the superiority of the Aryan race, the only one entitled to dominate the world, and also arouse in everyone the hatred of the Jews as a unifying element.

His work Mein Kampf (My Struggle) became a mass gospel, without being a treatise on politics, and the holy book of life and ideas of the supreme chief, without being any confession of the author, despite the title. As stated in it, the Aryan race is superior by nature; the State is the unit of “blood and soil”; The “Führer” (leader) is the incarnation of the State and therefore of the people … None of these ideas was new, but they also ended up causing the devastation of Europe, the cruelest defeat of the people who embraced them and the greatest genocide of the history.

Blood ties

The search for a family background that could justify Hitler’s imbalance led to the construction of various stories about his origins. The obscurity of the few real data and the unreliability of some of the data that he himself made in his book Mein Kampf contributed to this. Thus, it has been speculated about the possible alcoholism of his father, that he died confined in an asylum, or that his mother was a prostitute and had a Jewish grandfather. None of these hypotheses has been proven; It can only be stated with absolute certainty that Adolf Hitler was born on April 20, 1889 in Braunau am Inn, a border town in Upper Austria, and that he was the third child of the marriage formed by the customs inspector Alois Hitler and his third wife, Klara Pólzl.

It is assumed that his paternal grandfather was Johann-Georg Hiedler, a miller from Lower Austria who in 1842 married a peasant woman, Maria Anna Schicklgruber, who already had a five-year-old natural son, Alois, whose father was apparently none other. , than Hiedler himself, although he did not give him his last name. Almost forty years later, in 1876, Johann-Nepomuk Hiedler, brother of the previous one, appeared with Alois before the parish priest of Dóllersheim and asked him to delete the word “illegitimate” from the register and to register him as Alois Hiedler at the express wish of the father. Johann-Georg Hiedler had been buried for twenty years and the mother thirty, but the priest agreed. The year after his legitimation, Alois changed his surname Hiedler, of Czech origin, to Hitler, with a spelling similar to its phonetics.

Alois Hitler had joined the Imperial Customs Service at the age of eighteen and until 1895 he worked as an officer in different towns on the Austrian border. He had married 1864 with Anna Glass, a woman much older than him who died without having given him children in 1883. A month later, Alois Hitler married Franziska Matzelberger, who had already given him a son, Alois, and three months after the wedding gave him a daughter, Angela, the only one with whom Adolf Hitler had to maintain a relationship throughout his life, and with whose daughter Geli Raubal came to fall in love. This second wife also died shortly after from tuberculosis.

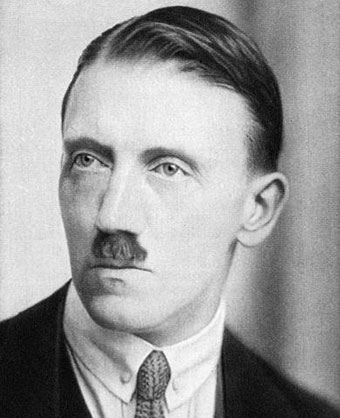

Hitler around 1920

In January 1885, Alois Hitler married Klara Pólzl in a third marriage. Gustav was born in May; both Gustav and a daughter born in 1887 died in infancy. In 1889 Adolf was born, and later Paula. Adolf Hitler was six years old when his father retired. The family then left Passau (their last destination), moved to Hafeld-am-Traun, then to Lambach and finally bought a house in Leonding, a village on the outskirts of Linz. Hitler spent his childhood there, which is why Linz was considered the “Führer’s hometown” and became a Nazi pilgrimage center. His father died on January 3, 1903, leaving a pension to his widow. Two years later, the mother sold the house for ten thousand crowns and they settled in Linz.

In the summer of 1905, the young Adolf dropped out of secondary education without pain or glory: his mediocre performance at the Realschule had earned him expulsion before winning a degree. When his mother died in 1907, he moved to Vienna with the inheritance money. He drew as a hobby and hoped to become an academic painter. He enrolled for the entrance exams at the Academy of Plastic Arts, but failed the entrance exam. The following year he collected his drawings and returned to the Academy, but this time the institution, after observing them, did not even admit him to examination.

From the military to politics

It was then, at the end of 1908, when Adolf Hitler came into contact with anti-Semitism through the theories of Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels. In the texts of this Austrian monk the germ of his later ideology is already glimpsed: Liebenfels called Arioheroiker (‘Aryan heroes’) to the blond race of lords, and confronted them with the inferior beings, the Affingen (‘ apes ‘), to conclude that the need to decimate the latter was biologically justified, since it would end the spawn of miscegenation.

During the whole of the following year, Hitler consumed a large quantity of these racist pamphlets. Even then he was living miserably, had exhausted his inheritance and was not working; he was staying in a homeless residence and starving on his wanderings in Vienna. He disregarded the repeated calls for military service, and at the age of twenty-four (the age at which the obligation to join the ranks ceased), he crossed the German border, settling in Munich. That same year (1913) the Austrian authorities found out his whereabouts and forced him to appear first at their consulate in Munich and then before the recruiting commission in Salzburg. There, given his weak physical condition, he was declared unfit and useless for the military.

Hitler (right) with his comrades in arms in WWI

The gradual gestation of his ideology had led the young Hitler to feel a deep contempt for the army of his native Austria, which he considered weak and irrelevant in the Europe of that time; instead he admired the vigor and strength of the German garrisons. It is therefore not surprising that, having avoided Austrian military service for three years, he voluntarily enlisted in the German army on August 16, 1914, shortly after the start of the First World War .

Wounded and gassed at the front, he was decorated with iron crosses for military merit of the second and first class, the latter honor very rarely granted in a rank like that of sergeant, which Hitler had achieved. According to testimonies, he was a brave soldier and soon gained the sympathy of his superiors thanks to his marked anti-Semitism. After the war ended with the humiliating defeat of Germany, Hitler saw the dreamed greatness of his adopted homeland and the camaraderie and other attractions of his adventurous life as a soldier vanish. He would still remain in the barracks for two years: he was appointed a propaganda officer of the Reichswehr, the regular army, and dedicated himself to preaching the nationalist ideal and the fight against the Bolsheviks among the soldiers, giving numerous lectures.

On September 12, 1919, he was commissioned to attend an assembly of the incipient German Workers’ Party (DAP) in order to gather information on said association. Hitler exchanged impressions with the president of the DAP, Anton Drexler, and it would all have ended there, perhaps, if he had not received a postcard shortly afterwards in which the leadership of the party (which then had no more than fifty members) communicated its entry into it. It was undoubtedly remarkable his affinity with that small ultra-rightist formation, which included among its ideological orientations the pan-Germanic expansionist ideal, anti-Semitic racism and the frontal rejection of the impositions of the Treaty of Versailles.

In March of the following year he left the militia to devote himself entirely to his political activity. It was then that the party added “National Socialist” to its name (becoming the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, National Socialist German Workers’ Party, from whose abbreviation the word “Nazi” would arise) and Hitler became its propaganda chief. As such, he managed to recruit prominent figures from Munich society, essentially nationalists, and also workers, contributing to the then modest growth of the group. In 1921, Hitler took over the presidency of the NSDAP, after eliminating Drexler; He soon established in the party some of his most visible traits: the cult of the personality of the “Führer” (“leader” or “caudillo”, that is, Hitler himself), the swastika and the salute with the raised arm.

Ludendorff (center) and Hitler together with other protagonists of the Munich putsch

In November 1923, following the example of Benito Mussolini in Italy, Adolf Hitler attempted the coup known as the Munich putsch. The two leaders of the attempt, Hitler and Erich Ludendorff, were arrested and tried; his failure earned him a five-year prison sentence, of which he only served eleven months thanks to pressure from his comrades. From that stay in the Landsberg jail came the first draft of Mein Kampf, dictated to Rudolf Hess, a cellmate also convicted of the attempted coup who would carry out high positions in Nazi Germany.

Once released, and despite the ideas expressed in the book (pan-Germanic expansionism, the doctrine of “living space,” the superiority of the Aryan race, and the extermination of the “inferior” races), no one prevented Hitler from reorganizing his party and continue his incessant propaganda work; he was just another hotheaded ultranationalist at the head of a fringe group.

The rise to power

But the economic crisis of 1929 and its trail of unemployment, deprivation and discontent among the middle and lower classes allowed the Nazi party a more than considerable development: from 2.6% of the vote in 1928 it went on to obtain 18.3% ( six million ballots) and 107 deputies in the 1930 elections. From that moment on the party began to receive aid from the Ruhr magnates (Von Thyssen, Otto Wolff, Voegeler) and other large industrial groups, which, like What had happened in Italy, they saw in the virulent anti-communism and anti-unionism of the Nazis an instrument that could drive away a workers’ revolution and dissuade the unions from their demands. In the two electoral processes of 1932, the National Socialist Party did not get enough deputies to govern alone, but it became the most voted force (37.3 and 33.1%). In January 1933, under pressure from the army and conservative sectors, the President of the Republic, Paul von Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor.

At a party march in Weimar (October 1930)

Once in power, Hitler systematically proceeded to liquidate the parliamentary system and any possible political opposition outside and within the ranks of his party, relying especially on the violence of the Schutz Staffel (the “Defense Squads”, better known for the acronym SS, the militarized police of the Nazi party). First, accusing him of the authorship of the Reichstag fire (February 27, 1933), he declared the communist party illegal, and after coming out of the March 1933 elections, in which he obtained 43.9% of the votes, he demanded to the Reichstag full powers for four years, which were granted with the opposition of the socialist party.

Parliament would no longer reflect ideological plurality, nor would new elections be called: Hitler immediately suppressed the trade unions and the other political formations. Following the steps necessary to finish off his opponents, he promulgated a law designed vaguely to reestablish “career functioning,” but which actually served to purge state services of Jews and Marxists, and generally to remove anyone who occupied it. a position coveted by the new Nazi bosses.

With Paul von Hindenburg, President of the Republic (August 1933)

After his first meeting with Mussolini (on June 14, 1934, in Venice), Hitler and the leadership of National Socialism (Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring, Reinhard Heydrich and Heinrich Himmler) got rid of their once appreciated Ernst Röhm and other opponents of the regime (Gregor Strasser, Kurt von Schleicher, Gustav von Kahr, at the head of a hundred). All of them were executed at point-blank range in the so-called “Night of the Long Knives” (June 30, 1934). Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen escaped the burning thanks to the protection of Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, still President of the Republic; however, he was about to resign from his post, went to Vienna as ambassador, and later continued to serve Hitler in Ankara.

On August 2, 1934, the elderly Paul von Hindenburg, President of the Republic, died. Hitler instantly promulgated a law that unified both ministries (presidency and chancellery) and became supreme head of the state; the army swore allegiance to “Führer and Chancellor Adolf Hitler.” At that time the SS had more than 100,000 men led by a fanatical ex-farmer who, according to some, surpassed the Führer himself in recklessness: Heinrich Himmler.

The Third Reich

Under the feint of the cult of duty and Prussian jargon, the new regime reflected the traits of its creator: disorderly but effective, energetic and centralized. Hitler was faithful to his Viennese customs: he got up at twelve o’clock, and was protected by a large number of private secretaries with ministerial rank who filtered their visitors, he received only whoever he wanted and only for a couple of minutes. His vitality appeared during the night when his terror of loneliness led him to maintain extensive monologues until dawn.

There were no government meetings. Laws were enacted by his terse orders, and later only a capricious observation would suffice. His stalwarts wrote down all his spontaneous occurrences and transmitted them to the nation as orders from the Führer. There is an anecdote in this regard that, founded or not, is certainly illustrative: in front of the church of San Mateo in Munich, Hitler warned his companions that the next time he did not want to see “that pile of stones.” The Führer was referring to a pile of cobblestones that were stacked near the entrance, but his observation was interpreted as an allusion to the church, which was simply demolished the next day.

Hitler in his first meeting with Mussolini (Venice, June 1934)

This is how the mechanisms of the government of a nation of seventy million inhabitants worked, and despite everything, they worked; thanks to his intuition, his nose and his systematic choice of viable solutions. His social policy had an extraordinary effect on the masses. He ordered measures that, according to him, contrasted with “theoretical socialism” the “socialism of the facts”: loans “to marriage” that promoted the creation of new families; protection and rest for mothers; massive sending of children (the first year 370,000) to vacation colonies; cottages, nurseries; works with such strange names as “winter relief”, “home”, “strength through joy”, and campaigns with titles such as “good lighting”, “green areas in the company”, “popular education”, “department of the leisure “or” beauty of work “,

Meanwhile, Heinrich Himmler was detaining half a million people in the twenty concentration camps and the one hundred and sixty labor camps. Subsequently, millions of Jews, Poles, Soviet prisoners of war, suspected of Semitism and subversives would pass through the camps to perish in the gas chambers or be annihilated by work. Countless testimonies would appear after the war of both the monstrous atrocity of the Nazis and the innocence of their victims, starting with the famous Diary of Anne Frank. First clandestinely, then more openly, the extermination responded to the objectives set out in Mein Kampf. And also its foreign policy; Like Mussolini, Hitler aided the coup general Francisco Franco in his fight against the Spanish Republic. Then he camouflaged, under the name of “struggle against Bolshevism,” the alliance with the dictators. Achieved with the constitution of the Berlin-Rome-Tokyo Axis the accession of Japan, could threaten the rear of the Soviet Union, which, with France, were its greatest threats.

Adolf Hitler (detail of a portrait by Heinrich Knirr, 1937)

Determined to carry out the pan-German ideal by force, Hitler had withdrawn Germany from the League of Nations in 1933 and promoted the strengthening and modernization of the army, ignoring the limitations imposed unilaterally by the victors in the Treaty of Versailles; at the end of 1937 he resolved to reunite all the German-speaking countries and territories before the Western powers had just rearmed themselves. To the alarm of the more conservative wing of the army, hostile to the SS, he disposed of Blomberg and Von Neurath and dismissed the commander-in-chief of the Wehrmacht, Werner von Fritsch, accusing him of homosexual, and the chief of staff Ludwig Beck, assuming command himself.

Certain of the Duce’s accession, in March 1938 he seized Austria. In September, counting in his favor with the fear of war and communism of the western democracies, he obtained the signing of the Munich Agreement, with which he won a quarter of Czechoslovakia. On March 15, 1939, with the Slovak secession already organized, Hitler ignored the agreements and occupied not only the Sudetenland but also the rest of Czechoslovakia, where he established the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. It also invaded the territory of Memel (Lithuania) and from April claimed the German districts of Poland. At the same time, it reinforced its alliance with Italy through the Steel Pact of May 22 and signed the Ribbentrop-Molotov agreement with the Soviet Union (August 23, 1939). a non-aggression pact that ensured the non-intervention of the Russians in exchange for the partition of Poland. On September 1, 1939, Hitler ordered the invasion of Poland, unleashing World War II.

The Second World War

The first phase of the war, known as the “blitzkrieg” (from September 1939 to May 1941), revealed not only the German arms power, but also the superiority of the strategy that gave it that name: instead of mobilizing Heavily large contingents of soldiers to the front, German aviation, tanks and battle tanks penetrated as decisive shock weapons into enemy territory, making way for the infantry and moving swiftly through the unprotected rear towards their final objectives. In less than two years all of Europe, including France, was subjected to Hitler’s rule: Poland, Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, France, Yugoslavia and Greece fell successively into the hands of the Reich; the remaining countries were either allies of Germany or neutral. After an aerial battle that had not borne the expected fruits, only England resisted. Hitler then made the mistake of turning his eyes to Russia.

Violating the non-aggression pact signed with Stalin, on June 22, 1941 he attacked the Soviet Union; after a dizzying advance, the failure in front of Moscow led him to take command of the ground army himself. With the Russian campaign and the bombing of Pearl Harbor, which marked the entry into the war of the United States and Japan, the “total war” began (from June 1941 to June 1943). Still, at the end of 1942 his company was successful. That year the “final solution to the Jewish question” had already been announced, albeit veiled, and mass murders of Jews were taking place across Europe. New camps had just been built in Poland: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chelmno, Majdanek, Treblinka, Sobibor, Belzec. Including Russian Jews, the least pessimistic estimates put the casualties at more than four million people.

Hitler announces the declaration of war on the United States in the Reichstag (December 1941)

On September 10, 1942, the maximum expansion of the Germans in the Soviet Union had been achieved. In November the allied forces landed in Morocco and Algeria, and in January 1943 the Anglo-American Conference in Casablanca demanded unconditional surrender. A month later, on February 2, 1943, the German army was to surrender at Stalingrad; this defeat, which certified the failure of the Russian campaign, reversed the course of the contest. With the incorporation of the formidable industrial and military potential of the United States and the USSR, time was running in favor of the allies; lost the opportunity for a quick victory, the Germans no longer had a choice. The final phase of the war (from July 1943 to 1945) was that of the retreat and collapse of the Axis powers on all fronts.

During the following months, in effect, the German power was declining overwhelmed by different events. In April and May 1943 the resistance rebelled in the Warsaw ghetto and the Afrika Korps capitulated in Tunisia. In July the Allies entered the phase of massive bombardments on Hamburg and destroyed great part of the city; on July 10, the English and Americans landed in Sicily, and on July 25, 1943, Mussolini fell. Italy then declared war on Germany. On December 1, the top Soviet leader, Iosif Stalin, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and American President Franklin D. Roosevelt, meeting at the Tehran Conference, they coordinated their war strategies and began to design the new map of Europe. In June 1944 the Allies landed in Normandy.

Hitler harassed, also suffered a planned attack by a group of officers when he was at his headquarters in Rastenburg (East Prussia) and was slightly injured. In revenge, he had at least two hundred resisters executed from the political-military elite; Günther von Kluge and Erwin Rommel committed suicide. On September 25, 1944, he appealed to the popular forces as the last attempt to protect the Reich. Worn out by defeats, he was already just mentally ill. However, he still believed in the triumph, which he hoped to obtain through secret weapons in the process of preparation, and he still supervised a last and desperate German offensive in the Ardennes, deactivated by the allies after six weeks of heavy fighting (January 25, 1945) . Then he returned to the chancery bunker.

After the Rastenburg attack (July 20, 1944)

Totally isolated, with the exception of Joseph Goebbels, his mistress Eva Braun and a small court of sycophants, in April 1945 Adolf Hitler watched as his once faithful servants tried to abandon him: Hermann Göring, who was trying to hasten the inevitable end; Heinrich Himmler, who even tried to contact the enemy … True to himself, as he put it in 1939, he would never utter the word “capitulation.” On April 13, he toasted Göring for the death of his despised Roosevelt. On the 20th he again toasted his few followers for his fifty-sixth anniversary. The Russian troops, meanwhile, continued their inexorable advance towards Berlin.

In the early morning of April 29, 1945, Hitler ordered a civil registry official to appear before him and made contact with Eva Braun, his “faithful student.” He had met her when she was an employee of Hoffmann’s shop, his photographer, in 1929, two years before his first love, Geli Raubal, the daughter of his stepbrother, committed suicide at Hitler’s home in Munich. Hitler and Eva Braun had already planned to kill themselves when they decided to join. The Führer had just received the news a few hours ago of the execution of Benito Mussolini in front of Lake Como. Then he had ordered that Blondi, his German shepherd, be poisoned. At the end of the ceremony, he dictated a political will in which he named Admiral Karl Dönitz President of the Reich and supreme head of the army. The next day, around three in the afternoon, a gunshot was heard: Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun had died, he from a shot in the mouth, she from ingestion of a cyanide capsule.

While in compliance with his provisions the two corpses were consumed by flames in the garden of the bunker, Martin Bormann communicated by radio to Dönitz that Hitler had appointed him his successor, but concealed the death of the Führer for another twenty-four hours. During this period, Bormann and Goebbels attempted a new negotiation with the Soviets; but it was a futile effort. Then they telegraphed again to Dönitz informing him of Hitler’s death. The news broke on the radio on May 1 with background music by Wagner and Bruckner, hinting that the Führer had been a hero who had fallen fighting to the end against Bolshevism. That same night, Nazi leaders and senior officials undertook a massive flight; there were many who managed to escape from Berlin. Goebbels preferred, after poisoning his children, kill his wife with one bullet and commit suicide with one shot. On May 7, 1945, the capitulation was signed in Reims, and on the 9th the signing was repeated in Berlin. On the same date, all hostilities on the European fronts were suspended. The Third Reich had outlived its creator for exactly seven days.