Despite the efforts of his biographers, a legendary fund is still hovering over the figure of Walt Disney (1901-1966). A repeated rumor assures that Disney was a European emigrant, probably Spanish, who arrived in the United States and that, later, out of fear of suspicion, he falsified his origin. The circumstances of his death have also been mythologized: many believed that Disney had been frozen with modern hibernation techniques.

Walt Disney

According to this legend, his body would still remain like this with his vital signs suspended, waiting for a future in which he could wake up and new surgical procedures would repair his health. But the prosaic reality is that the Disney corpse was cremated at the wish of his relatives. It is not surprising, however, all this mixture of reality and fantasy around who went down in the history of Western culture as one of the most prolific, contradictory and influential cultivators of children’s imagination.

Walter Elias Disney was born on December 5, 1901, in Chicago, Illinois. Fourth of the five children that Elias and Flora Disney had, their childhood passed between financial difficulties and under the severity of their father, a carpenter by profession, who tried his luck in all kinds of businesses without ever improving his battered economy. Eternally despised by his father, Walt grew up close to his mother, a former teacher of German descent, and to his brother Roy, eight years his senior.

In 1906, Elias Disney decided to start a new life on a farm near the small town of Marceline, Missouri, where Walt discovered nature and animals. Also then his interest in drawing was born, which he shared with his little sister, Ruth. Elias Disney made his sons work so hard maintaining the farm that the two oldest, Herbert and Raymond, decided to leave home to settle on their own again in Chicago.

The difficult beginnings

The precarious situation in which the family was left with the departure of the two young men worsened in the winter of 1909 when the father contracted typhoid fever and the disease forced him to sell the farm and move to Kansas City, Missouri, where he found a job as a Newsboy, a task in which Roy and Walt helped him. This meant a lower performance of little Walt in school, where he was never an advantageous student. After a couple of years, Walt, who occasionally made some money selling his cartoons, enrolled at the Kansas City Art Institute, where he learned his first notions about the technique of drawing. In those years of his adolescence, he discovered the cinema, an invention that he was passionate about from the first moment.

During the war he was an ambulance driver

(the drawing on the canvas is from Disney himself)

In 1917, five years after Roy Disney also left his parental home, Elias Disney moved with his wife and two young children back to Chicago, where he tried his hand at setting up a small jam factory. In the spring of 1918, Walt, with only seventeen, falsified his birth certificate and enlisted as a soldier in the Red Cross to fight in World War I. He arrived in Europe when there was already peace, but he was stationed in France and Germany until September 1919. Once he graduated, he went to live with his brother Roy in Kansas City, where he sought employment as a cartoonist.

His dream was to become an artist for the Kansas City Star, the newspaper he had circulated in his childhood, but he found work as an apprentice at an advertising agency, the Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Studio. With a salary of $50 a month, in that job he met Ub Iwerks, a young man his own age and exceptionally gifted in drawing, with whom he became friends. When the two lost their jobs, they started their own company, the Iwerks-Disney Commercial Artists. The company lasted only a month, as Walt preferred to accept a secure job, although he convinced his new bosses to hire Iwerks. In that job, they both learned the techniques, still very rudimentary, of cinematographic animation.

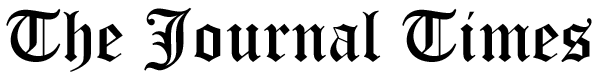

The tireless Walt Disney at work

Restless and innovative by nature, Disney borrowed a camera and set up a very modest studio in his garage, where with the help of Iwerks and working nights, they produced their first animated film. The film was accepted and they got new commissions until Disney, who was not yet twenty-one years old, convinced Iwerks to try their luck again as entrepreneurs with a company they called Laugh-O-Gram Films. With production based on traditional tales, things went well for them until the bankruptcy of their main client dragged them into bankruptcy as well.

To hollywood

In 1923, after trying in vain to overcome the pothole, Disney emigrated to Hollywood. The burgeoning movie industry had made Hollywood a land of promise. Disney believed that with his experience as a cameraman he would get a job as a director, but no studio wanted his services, so he decided to re-start his own company with his brother Roy as a partner. On October 16, 1923, the Disney Brothers Studio signed its first major contract, but still insufficient to deal with its financial difficulties. Already then, Walt revealed what would later become a constant in his company: that he was capable of resorting to any stratagem to get the business forward. In 1924,

Walt Disney (in the background) with a team of cartoonists

On July 13, 1925, three months after his brother Roy married, Disney married Lillian Bounds, a young employee of his studio, with whom he had two daughters: Diane Marie, born on December 18, 1933 when the marriage already ruled out that they could have children, and Sharon Mae, whom they adopted in 1936. In the spring of 1926, and after having to change premises because the company was growing, the two brothers changed the name of their company, which was renamed the Walt Disney Studio. But the studio suffered a major setback when its main client got the rights to the rabbit Oswald, a character created by Disney who had starred in several short films.

The Triumph of Mickey Mouse

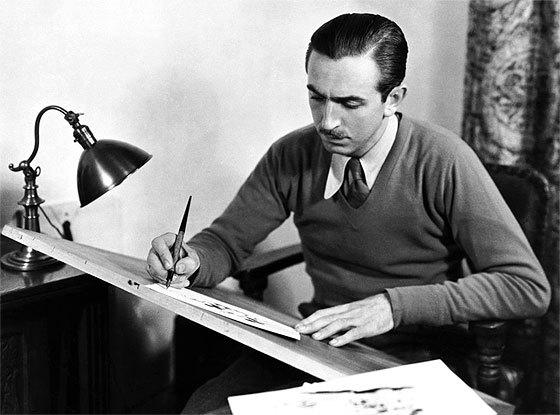

Determined to eliminate intermediaries from now on, Disney conceived (during a train ride from Hollywood to New York) Mortimer, a little mouse later renamed Mickey at the suggestion of his wife and who Iwerks shaped. This is how Disney told it, but, in reality, the paternity of Mickey Mouse has always been a matter of controversy, and currently, Iwerks himself tends to attribute himself. In October 1928, when Disney was looking for a distributor for the two films it had produced with Mickey Mouse as the main character, the first talkies film was screened. In anticipation of other producers who thought the innovation was fleeting, Walt was quick to incorporate the sound into a third Mickey film, Willie on the Steamboat.(1928). A good impersonator of voices and accents, Disney made the mouse and his girlfriend, Minnie, speak with their own voice to cut costs. The film, released on November 18, 1928 in a New York theater, was a resounding success with the public and critics.

Still from Willie on the Steamboat (1928)

In 1929, with his exceptional sixth sense for business, he authorized several companies to reproduce the image of Mickey Mouse on their products, incorporating white gloves and shoes to prevent hands and feet from disappearing on dark backgrounds. On January 13, 1930, a cartoon of the popular character (with Disney as a scriptwriter and Iwerks as a cartoonist) began to be published in various newspapers in the United States, and that same year a book of Mickey’s drawings was published that was reissued on numerous occasions.

Addicted to work, for which he stole many hours of sleep, Disney had a serious health crisis that forced him, at the end of 1931 and when the Mickey Mouse club already had a million members, to take a long vacation with his wife. Back in Hollywood, he joined a sports club where he practiced boxing, calisthenics, wrestling, and golf. Soon after, he discovered horse racing and, finally, polo, of which he was a fanatic for the rest of his life. A hobby that he cultivated with as much passion as his fascination for trains and miniatures.

With Mickey Mouse as the flagship of a company on the rise, Disney believed that it should not rest on its laurels or get bored making only films of the famous mouse, which in 1932 was the first of the Oscars he would receive during his career. Backed by a team of excellent cartoonists and illustrators, he displayed all his creative spirit in the first series of his Silly Symphonies (1932). Made in technicolor, the various short films that made up this production were an experiment in the expressive use of color in its time. In November of that same year, the Disney studio became the first to have its own school for cartoonists and animators.

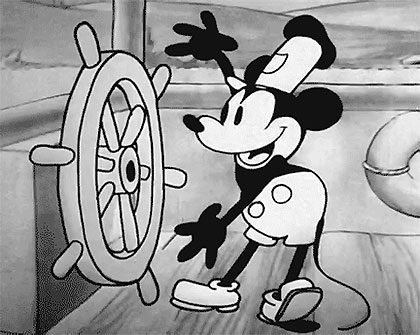

Disney in an image taken in 1940

A year later, on May 27, 1933, he premiered the silly symphony that made number thirty-six and that was to have an unexpected success: The Three Little Pigs. Without intending it, his famous song Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? it became a song of hope for millions of Americans trying not to be eaten up in real life by the Great Depression. In 1934, when his studio had 187 people, Donald Duck was born, a character with an irascible and perverse character, who came to join the dog’s Pluto and Goofy.

The feature films

When he had already made a name for himself in the Hollywood industry, Walt Disney embarked on a risky and unprecedented endeavor: to produce the first animated feature film in the history of cinema. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) proved not only that Disney and his team were virtuosos at animation, but that cartoons could be a whole film genre. The film raised four million dollars, a record for the time, but it left Disney in debt until 1961 because of the amortization of the credits it had to ask for since the initial budget of $500,000 for the film had ended up tripling.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937)

In Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the multiplane camera was used for the first time, capable of suggesting the depth of field thanks to an ingenious superposition system of five sheets filmed on the same plane to simulate distance and a new technicolor system. The film was the first example that the animated cinema of the Disney school had a solid narrative procedure, in which human characters were described from the “gaze” of humanized animals or fantastic beings. Also evident in the film was Disney’s taste for the dark and his style of suggesting rather than openly showing terror.

The 1940s were a period of great activity at Disney, characterized both by the consolidation of the style that began with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and by the contradiction that Walt felt between his artistic tendency to innovation and risk and the need to cater to a market not given to novelties and experiments. A reflection of this was the lukewarm response of the public to the following films coming out of their “factory” of dreams. Pinocchio (1940), considered one of the masterpieces of animated cinema by critics and in which $2,600,000 was invested, was a commercial disaster.

The same happened with Fantasía (1940), which cost $2,300,000. In it, cartoonists and animators combined the evolutions of cartoon characters with the music of Stravinsky, Dukas, Beethoven, Ravel, Bach or Tchaikovsky. Considered a masterpiece by some and an insulting caricature of classical music by others, Fantasia was not the “total work” that Walt Disney had envisioned and desired. These business failures opened a significant economic gap in the company, alleviated shortly after by the consecutive successes of Dumbo (1941) and Bambi (1942).

Fantasy (1940)

After the sketch on The Dance of the Hours, by Amilcare Ponchielli, which he co-directed with Norman Ferguson in Fantasia using the pseudonym T. Hee, Walt Disney left the field of filmmaking to dedicate himself almost exclusively to the task of directing the fledgling empire. the film into which the company he had so modestly started fifteen years earlier had become. On May 6, 1940, he completed the construction of his new Burbank studios, which earned him the nickname “Wizard of Burbank.”

Designed by himself with the aim of facilitating the work of his employees, those studios had twenty large buildings, separated by streets that were named after their characters. The company’s workforce numbered around 2,000 employees, from whom Disney demanded a high level of creativity and production in exchange for very low salaries, although he never spared any expense when making his films and always personally led a no-frills private life. no ostentation.

Angry anti-communist

On November 10, 1940, he began to collaborate with the FBI, after the then director of the federal investigative agency, J. Edgar Hoover, had tried on several occasions to recruit the film producer as an agent to provide him with any information or details. on the presence of subversive elements (communists, trade unionists or anarchists) in Hollywood. However, Disney’s early political flurries had a more progressive look, dating back to 1938, when it joined the Society of Independent Motion Picture Producers, an association of independent producers and filmmakers opposed to the absolute dominance of the big Hollywood studios. From that group, which had figures like Orson Welles or Charlie Chaplin Disney was drifting towards an ideology close to the North American Nazi party and a strongly anti-Marxist sentiment.

In 1941, a newly created illustrators union at his company threatened the “Wizard of Burbank” with going on strike demanding better wages. Disney personally tried to avoid the conflict by directing a speech to his employees, but they, to his amazement, since he conceived the company as a great family, did not let him pass the first sentences. On May 29 of that year, the Disney studios were almost paralyzed by a strike in which most of the workers participated and which lasted a whole year. The conflict ended when the company agreed that workers could freely choose their union, including the left-wing Screen Cartoonists Guild.

Walt Disney in 1941

The agreements that led to the end of the strike were signed by Roy Disney, as Walt was traveling to various countries in South America. From that long trip, several films came out, aimed basically at the Latin American public. Among them, Saludos, amigos (1943) and Los tres Caballeros (1945), in which he combined cartoons and real-life actors. In 1943, many of his best cartoonists left him to found the UPA (United Productions of America), where, among others, the myopic character of Mister Magoo would be born.

After the end of World War II, in which Disney had agreed to film propaganda films for the US government, he left the presidency of his company, handing over the position to his brother Roy, but only kept that decision for a few months and at the end of 1945 he returned to occupy the presidential chair. Upon returning, he laid off more than 400 employees, assuring that the company was going through a crisis and had to comply with the agreement reached with the Screen Cartoonists Guild to grant the 25% salary increase to cartoonists.

Reaffirmed in his anti-Marxism and collaborator of the FBI until his death, Disney promised to abort any element that would attempt against the North American nation at the meeting held on November 24 and 25, 1947 at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York, which culminated in the so-called Waldorf Declaration, in which many film producers pledged to collaborate with the Commission on Un-American Activities in the “witch hunt.”

In August 1948 he made a trip with his daughter Sharon to film images in Alaska, and with the material, he made the series of shorts entitled Real Life Adventures. His brother Roy opposed the project (by then they were already so far apart that they only saw each other after making an appointment with their respective secretaries) and predicted an uncertain destination for this type of documentary. He was wrong, since the first of them, entitled The Island of the Seals (1948), not only turned out profitable, but was awarded an Oscar in the category of short films.

Almost at the end of the 1940s, Disney received an interesting proposal from Howard Hughes: an interest-free loan of one million dollars in exchange for his help in a field (the film sector) that the Texan billionaire did not know and in which he wanted to invest. With that money, Disney started 18 new projects, including Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951) and Peter Pan (1953). After a very expensive foray into futuristic cinema with 20,000 leagues of underwater travel (1954), he returned to cheaper projects that tune in with the pride of being an American.

By then, his company was no longer the queen of cartoons. Warner Brothers were beginning to give him serious competition with the star of its Looney Tunes series, Bugs Bunny. That rabbit was the counterpoint of the candid, apolitical and sexless Mickey Mouse, who in the early 1950s lived his lowest moments of popularity, although he remained the favorite character of Disney and the emblem of his empire.

Disneyland

In 1953, after winning a new Oscar for best documentary with The Living Desert, he began conversations with the ABC television network to cede the broadcast of his films to the new invention. Unlike other Hollywood producers, who considered it a threat, Disney believed that television was an excellent means of disseminating its products. A year later, he began making films specifically for television, the part of his artistic production most reviled by critics. Criticisms that would also rain years later with Mary Poppins(1964), his first feature film with only real actors. But Disney did not care, because those films gave him the money he needed to make a project he had cherished for a long time: building a huge amusement park based on his characters.

Disney and Von Braun (1954)

Workaholic and perfectionist, the film producer designed down to the last detail for Disneyland, which opened on July 17, 1955 in Anaheim, California. This park, with an area of 120 hectares, cost 17 million dollars, and Main Street USA, its main street where hundreds of actors dressed as characters walked, perfectly recreated the main street of Marceline, the town where she lived her childhood. Disney, who that summer of 1955 was already the grandfather of the first of the ten grandchildren he had.

A billionaire and winner of twenty-nine Oscars, in the 1960s he had established himself as one of the best known and most loved characters in the world, but his health was failing, and his entire empire entered a struggle for succession. A chain smoker and alcohol fan, he died on December 15, 1966 in Los Angeles, California, a victim of lung cancer, after having supervised the sketches of Disney World, a Disneyland-style theme park but more focused on adults. which would open its doors in 1971 in Orlando, Florida (in 1983, the company opened the Tokyo Disneyland in Japan and in 1992 the Euro Disney in Paris opened its doors).

The “Wizard of Burbank” had died without actually seeing The Jungle Book (1967), the second most commercial Disney film since the time of Snow White, directed by Wolfgang Reitherman, who took over the production of the Disney animated feature films. until 1981. After years of high production and few notable successes, Disney studios once again became the kings of the cartoon genre with Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992) and The Lion King(1994). With the death of Disney, one of the fundamental names in popular culture of the 20th century entered the legend. With varied fortune, they would try to replace him with such disparate figures as his brother Roy O. Disney, his nephew Roy E. Disney and his son-in-law Ron Miller. But only executive producer Michael Eisner proved himself a worthy successor.