Depending on whether or not his doctrine is shared, Luther is an apostle or at least a prophet for some, and for others a renegade heretic. Destroyer of endless things, this man of intense and energetic convictions represents, with his conception of man as an individual isolated from God, from history and from the world, one of the pillars on which the Modern Age rests. Initiator of the Reformation (period of two centuries of wide European repercussion in the history of Christianity, the origin of the Protestant Churches and the Counter-Reformation), Martin Luther rejected the authority of the pope and weakened the power of the Church. The abolition of purgatory, from which souls were liberated with masses, the rejection of the doctrine of indulgences, which would considerably reduce the pope’s income, and, above all, the doctrine of predestination, which makes the soul independent from The action of the clergymen after death (to which must be added the recognition of every Protestant prince as head of the Church of his country), forced to present the Reformation as a great revolution of the less civilized nations against the intellectual dominance of Rome.

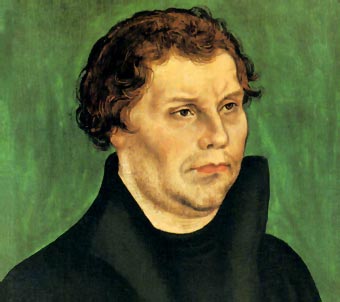

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was born on the night of February 10-11, 1483 in Eisleben, in Thuringia, a region dependent on the electorate of Saxony. As time went by and having just won the title of doctor, Martín would change Luder’s surname to Luther’s, deriving it from Lauter, which in old German means “clear, limpid, pure.” He was the first-born of the nine children of Hans Luder, a miner, the son of peasants and a good Catholic, and Margarethe Ziegler, a hardworking woman, very pious and devout, who instilled in her son such dark piety that it left deep sadness in his soul. Both parents were from a poor family and very severe.

One year after the birth, the father was hired in a copper mine in Mansfeld, and the family’s situation, which was extremely precarious, improved somewhat, without becoming in any way buoyant. At Mansfeld, Luther received many of the beatings that his parents gave him, although, in Luther’s own opinion, “they always wanted my good; his intentions for me were always good, they came from the bottom of his heart. From his letters, we know that he was often subjected to cruel punishments, such as once his father whipped him so violently that the young man ran away from home and took a long time to forgive him in his heart, or on another occasion when his mother beat him up. make him bleed for having eaten a walnut without permission.

The harsh treatment to which they subjected him would turn him, according to his friends, into a sullen and distrustful being. The school, from the age of six, did not treat him better. He also received lashes from the teacher, fifteen in one day, as he later recounted, since “our teachers behaved towards us like executioners against thieves.” At the age of fourteen, he left Mansfeld for Magdeburg to study at the Latin school, and a year later he left Magdeburg and moved to Eisenach, home to his maternal grandparents. There, in his “beloved city,” he received solid instruction from a master poet named Hans Treborio, who had replaced the whip with good manners.

On July 17, 1501, he enrolled in the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Erfurt, upsetting his father for the first time, who wanted him to study law. On September 29 of the following year, he graduated with a bachelor’s, a first degree from the university, with the number thirty of a class of fifty-seven names. At the age of twenty-two, he has proclaimed a teacher of philosophy. This time it was the second of seventeen and his father, admired at the superiority of his son, stopped being familiar with him. From that moment on, the young teacher would dedicate himself with determination to the study of theology and with a passion to Sacred Scripture.

Luther in the habit of an Augustinian monk

On July 2, 1505, Martin Luther moved from Mansfeld to Erfurt to see his family. Halfway there, lightning struck his feet. The young man, who was extremely nervous and very sensitive, saw himself on the verge of death, was terrified and invoked the patron saint of the miners: “Save me, dear Saint Anne, and I will become a monk,” he exclaimed. Then he glimpsed in the sky a fantastic figure, which due to the excitement of the moment he could not identify. It was the first of the visions that he would have throughout his life, in the most unlikely and, at times, inappropriate places. Fifteen days later, he appeared at the Augustinian convent in Erfurt to fulfill his promise, a decision that so irritated his father that he once again referred to him. Without parental consent, then, he entered the convent. Novice first with the name of Augustine,

In order to study theology and occupy a chair at one of the many German universities run by the Augustinians, in 1508 his friend and spiritual adviser Johan von Stanpitz, then vicar general of the Augustinians, sent him to the University of Wittenberg to study a course on Aristotle’s ethics. In 1509 Luther obtained the title of Baccalaureus Biblicus, which granted him the right to practice biblical exegesis publicly. A young professor at the newly created University of Wittenberg, he would soon show great intemperance and daring in his manifestations, at the same time that he felt beset in his privacy by grave scruples of conscience and devastating temptations.

The forging of a thought

Around that time, an old Augustinian friar recommended him the consoling reading of Saint Paul, in whose study he eagerly engaged to deduce from it the first seeds of his dramatic dissidence with religious orthodoxy. The Epistle to the Romans of Saint Paul found an answer to his anxieties about salvation, understanding that man finds his justification in the grace of God, generously granted by the Creator regardless of his own works. Paradoxically, it was in that not a very reassuring idea that only faith and not merits save, an individualistic doctrine that condemns man, in a certain way, to abysmal loneliness, that Martin Luther found a certain peace and spiritual certainty that would move him to an irreducible diatribe against the Vatican, to temper its turbulent character in a perennial battle and to found the new Protestant doctrine. His teachings soon attracted attention. He also began to preach; his eloquence drew crowds and would earn him the consideration of being the first preacher of the time.

Sale of indulgences

In 1510, Luther made a trip to Rome in the company of another Augustinian to present to the general of his order certain complaints about the strict observance of the monastic rule. The result and the impressions of the trip could not have been direr for the restless and rebellious soul of Luther. The immediate consequence was to create in him a definite aversion to Rome, to the atmosphere of corruption and relaxation of the Roman clergy, to the decadence into which the entire Vatican had fallen, and to the excess of pageantry and wealth that the Holy See displayed, with prelates and popes more attentive to material aspects than to spiritual ones. Annoyed by the spectacle, Luther became acidly critical of the spectacle of degradation that reigned in the city of the popes and less affected by the obligations attached to his state.

Back in Wittenberg, he received his doctorate in theology on October 18, 1512, although his work shows the enormous detachment he felt for the philosophy and scholastic theology prevailing in his time. He was hardly interested in the great thinkers of the thirteenth century ( Thomas Aquinas, Saint Bonaventure or Juan Duns Scotus ), although he explored the Bible and some of the writings of Saint Augustine of Hippo with passionate intensity.. Also appointed, much to his regret, subprior of the Wittenberg convent, Luther began to teach at the university in which he interpreted and studied the Holy Scriptures, with a special interest in the Pauline work. At that time, he finished shaping and polishing what would be his theological cornerstone, justification by faith, according to which the Christian could save himself not by his own efforts or merits, but by the gift of God’s grace, so widely accepted. only by faith in Jesus Christ the Savior.

Luther also reached another conclusion just as important and transcendental for the future of his reform: it was necessary to submit completely to the Holy Scriptures and reject any other interpretation from outside. The gospel they had been directly inspired by God; no interpretation could be reliable on its own. Suspicion of the authority of the pope as supreme head of the Church and as an infallible person was the next step, which Luther took at once. It was then that he transformed his surname and began to think of himself as the “man of Providence called to illuminate the Church with a great splendor.” At the moment he had little influence. He was only, at thirty-four years old, an eloquent and famous professor at the University of Wittenberg who held important positions both in the convent and within the order; but he felt personally responsible for the Saxon faith.

In those years he assumed the position of vicar of his district, which meant the direction of eleven convents, to which had to be added his lessons at the university and the government, the economic administration and the spiritual direction of his convent in Wittenberg. Overwhelmed with work, in just two days he even visited all the convents that were under his rule, staying in one of them for barely an hour. He slept barely five hours on a hard platform, although he enjoyed the pleasures of the table with the same immoderation that characterized him throughout his life. Sometimes he locked himself in his cell to pray the offices seven times and thus make up for the negligence he had incurred during the week, beset by his occupations.

The rebellion of indulgences

In 1513 Juan de Medici had started his pontificate with the name of Leo X; Embarked on the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, the new pope enthusiastically promoted the sale of indulgences. Luther, who had already begun to express his personal ideas on the foundations of the faith, rose up in his speeches against that practice. Scandalized by what he considered to be a poisoning and spiritual scam of ordinary people, he tried to alert the German ecclesiastical authorities, but, meeting the most absolute silence at all levels, decided to act on his own.

The ninety-five theses

Obsessively inspired by some words of Saint Augustine (“what the law asks, faith achieves”), he wrote his famous ninety-five theses against the sale of indulgences and determined them to the most visible place in the city, in the door of the portico of the Church of All Saints of Wittenberg, on October 31, 1517. The incendiary theses, full of diatribes and direct attacks on the Church of Rome and the pope, were first written in Latin, for, soon time, to be translated into German and reproduced by the printing press, at the same time that they spread with extraordinary speed thanks to the work of the students.

It was a declaration of war that Rome could not leave unanswered. The resonance of the event was enormous despite the fact that Luther, from the pulpit and the classrooms, tried in vain to soften the situation he had created by appealing to a traditional doctrine accepted in the Church, according to which the nullity of indulgences was accepted to save souls, since this prerogative only belonged to God. The Dominicans, in charge of the Inquisition, denounced Luther before Rome, for which he was ordered, the following year, to appear in the Eternal City to answer the charges that had been formulated against him. Luther displayed great cunning and managed to involve the political power in the dispute by asking Prince Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony,

Pope Leo X

In the month of October 1518, Luther went to the city of Augsburg to discuss his position with the papal legate Cayetano de Vio, who had in his possession a brief from the pontiff Leo X by which Luther had to publicly retract his serious errors or, otherwise, be taken to Rome arrested. Under the political protection of Prince Frederick, Luther prolonged his discussion with the papal legate for four days without either party giving up their respective positions. And not only did he not recant, but he starred in a shouting match with the cardinal. The cardinal would affirm: «I don’t want any more dealings with that animal. He has glaring eyes and puzzling reasoning. Luther hardened his position by stating that the infallibility of the Holy Scriptures was above that of the pontiff himself.

After leaving Augsburg unscathed, Luther sent out an appeal under the title From the misinformed pope to the best-informed pope, in which he appealed to a council chaired by the pope to express his reformist ideas. Since his safe retirement from Wittenberg, Luther managed to gather a kind of minor council in the city of Leipzig, held between June 27 and July 16, 1519, in which Luther affirmed that although the desired council did not give him the reason, he would not retract, since he was subject to the only legitimate authority, that of the Holy Scriptures.

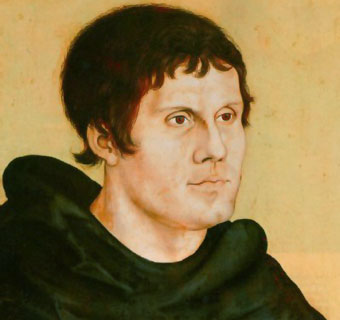

Leon X’s response was immediate. On June 15, 1520, the pope sent Luther the bull Exsurge Domine by which he ordered him for the last time to recant under penalty of ex-communication. After a futile attempt to address the pontiff so that he could celebrate the long-awaited council, Luther solemnly burned the bull together with a copy of the Corpus Juris Canonici in the presence of students and citizens of Wittenberg (December 10, 1520), and replied to the pope with the libel Against the execrable bull of the Antichrist. With such an act, Luther symbolically expressed his total break with the Church of Rome.

Luther burns the papal bull

On January 3, 1521, Leo X drew up the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem, by which Luther was definitively excommunicated. According to Ecclesiastical Law, the ecclesiastical excommunication had to be carried out by the secular arm, a task that fell on the newly elected emperor, Carlos V of Germany and I of Spain. The emperor took advantage of the meeting of the courts in the city of Worms, in April 1521, to summon Luther, where he was intimidated into recanting, but the wayward Augustinian monk remained stubborn in his heterodoxy and confronted all the dignitaries imperialists and ecclesiastics gathered there against him, fully convinced that the same fate awaited him as Jan Hus.

Charles V, pressured by the unstable political situation in Germany and by the fame and prestige that the heretical monk had already acquired, limited himself to prohibiting the practice of the new faith and declaring Luther and his follower’s outlaws. Subsequent efforts to change Luther’s mind proved futile. On May 26, Charles V signed the Edict of Worms; in it he ratified the sanction of exile for Luther and ordered the burning of all his writings.

Luther at the Diet of Worms

Precisely, the year before the conviction, Luther had brought to light, in German and aided by the powerful propaganda machine that turned out to be the printing press, his three fundamental works: The Freedom of Christianity , undoubtedly his best elaborated and written, in which he clearly outlined the pillar on which the new religion was based, salvation by faith in Christ; Appeal to the Christian Nobility of the German nation, in which he invited the nobility to assume their role as protector of the people and to join the Lutheran cause, in addition to instituting the three basic evangelical principles of Protestantism (universal priesthood, intelligibility of the Holy Scriptures and responsibility of all the faithful in the Church government); and, finally, The Babylonian Captivity of the Church , a work for theologians in which he rigorously analyzed the perversion process to which the sacraments had arrived, of which, according to him, only two should subsist, baptism and dinner (discarding transubstantiation). With these three works, Luther prepared his battle line at the same time that he laid the first foundations of a future evangelical Church.

To protect Luther, Frederick the Wise faked his kidnapping and hid him clandestinely in Wartburg Castle, in Thuringia, where the ex-monk found peace and the ideal retreat environment to fully indulge in a fruitful literary activity. Luther wrote numerous letters, continued with various psalms, wrote ecclesiastical glosses, wrote a work on confession, another on monastic vows, and a good number of others. And, furthermore, in the short year that he remained in Wartburg (from May 1521 to March 1522), Luther carried out his most important and transcendental literary production for the definitive implantation of the new faith: starting from the Greek text published in 1516 by Erasmus of Rotterdam, translated the New Testament into German. The edition would be called the “September Bible” for having appeared in that month, and made available to the German people their version of the sacred text par excellence. The work was such a success that many more copies had to be printed in December. Twelve years later, in 1534, he would put an end to his project by publishing his version of the Old Testament, translated from Hebrew.

Wars and weddings

The disorders that had arisen in Wittenberg by his more radical followers, who had begun to take drastic measures on liturgical matters, such as the suppression of the celebration of Mass, forced Luther to leave his peaceful retreat from Wartburg and return to Wittenberg, where he returned to take the reins wisely and in moderation, without losing your cool, but with determination. Luther took command in organizing the new evangelical communities that were springing up everywhere throughout Germany. From Wittenberg, Luther opened another front of struggle against the social and national liberation movements of the gentry and especially of the peasants. The former kept pressing for Luther to establish a German national Church, while the latter, Encouraged by the free interpretation of the Holy Scriptures defended by Luther, sought his support to alleviate the conditions of misery and subjugation in which they lived. His positions were radicalized to become a political issue that dragged Luther himself.

The Peasant Wars (1524-1526), led by a former Lutheran pastor, Thomas Müntzer (founder of the Anabaptist sect), were the culmination of the tense situation that the Reformation was undertaken by Luther had introduced in Germany. During the bloody war of the peasants against their lords, Luther failed in his attempts to appease spirits with his pen. Although deep down he supported a large number of their demands, when the peasants resorted to violence against the entire population as a whole, Luther did not hesitate for a moment to appeal to the nobles to restore the established order with arms, which gave cover to the bloody repression of peasants such as had never been seen in Germany. The conflict, which resulted in a real indiscriminate massacre, made Luther less popular among the most disadvantaged masses,

In 1525, in Germany devastated by the war of the peasants, Luther strove to demonstrate the servitude of the human will and wrote De servo arbitrio ( Of the enslaved will ), as a refutation of Erasmus’s defense of free will in his work De free will. It was also the year he chose to marry. In 1523, nuns escaping from the Nimchen Laz Grimma convent had arrived in Wittenberg. One of them, Katharina de Bora, twenty-six years old, became Mrs. Luther, in his Käte. The wedding aroused a lively rejection, not so much for the act itself as for taking place in moments of great desolation and death. The marriage would, however, be a success. Katharina of Bora, sixteen years younger than Luther, belonged to the gentry and was a sensible and intelligent woman who softened the exalted character of her husband and lived with him in perfect harmony.

Katharina from Bora

After her wedding, the Elector of Saxony gave her the old Augustinian convent in Wittenberg, where the industrious Katharina established a student pension to alleviate her financial straits to some extent. The students had the privilege of sharing the table with Luther, who after the collation condescended to answer their questions, as a result of which the book Dichos de sobremesa was born. In the Wittenberg convent, converted into a family estate, his six children were born one after another, of whom four survived: Hans, Magdalena, Martín and Paulus, who filled the preacher with joy. Doctrinally none of this should be surprising; a few years earlier, Luther had given birth to his work Opinion on Monastic Orders, a vibrant exhortation to monks and nuns to break their vows of chastity, a recommendation that was very well received, to the point that more than a few Augustinian religious of both sexes engaged in unions seen from orthodoxy as sacrilegious.

The consolidation of the Reform

The young Luther, of medium height, who had been “so thin and tired in the body that his bones could be counted,” grew fatter with age and new condition. His love of good food, and especially of beer, with which he replaced water (he was convinced that Wittenberg water was deadly), would make him a massive and heavy man, although he was still as lively as ever. The aggressive vulgarity of which he always displayed was accentuated and he used increasingly rude and rude words. He remained irritable; He could hardly control his angry and violent character. “I can’t control myself and I would like to rule the world,” he said of himself.

The new Church, which officiated the Mass in the vernacular, had since 1529 its catechism written by Luther ( Grosser Katechismus and Kleiner Katechismus, the great catechism and the small catechism), its own clergy and a large number of the faithful. The influence of the Reformation had spread across northern and eastern Europe, and its prestige contributed to making Wittenberg an intellectual center of the first order. The fierce defense that he made of the independence of the rulers with respect to ecclesiastical power earned him the unconditional support of many princes, to the point that from then on the Reformation became more a matter of kings than ecclesiastical, just one of the things that Luther had proposed from the beginning.

Luther in a portrait by Cranach the Elder (c. 1526)

When he was forbidden to attend the Diet of Augsburg, held in 1530, because he was excommunicated and unable to speak with the emperor, Luther delegated the reformist defense to the person of his most beloved and prepared collaborator, the humanist Philipp Melanchthon, who introduced the assistants the Augsburg Confession, a text written under the supervision of Luther that exposed the Protestant profession of faith and twenty-eight points of definite discrepancy with Catholicism. Two years later, Emperor Charles V, harassed by the struggle he had been holding with the Turks in the Mediterranean, had no choice but to compromise with Lutheranism by signing the Peace of Nuremberg, which established the freedom to exercise free and publicly the new cult on German soil.

When in 1536 Pope Paul III belatedly decided to convene the Council of Trent, Luther, arrogant and exalted, took for granted its uselessness, claiming the irreversible departure of both positions. To further reinforce such a dissident and intransigent position, Luther published the Articles of Schmalkalde, in which he exposed all the differences that had caused the separation of both churches. He placed special emphasis on the celebration of the Mass (abominable and superfluous for him) and on the role of the pope as the only person responsible for the calamitous state to which the Christian Church had reached.

Towards 1537, the health of Luther began to break progressively and alarmingly for his followers. The reformer grew old and his mood turned sullen. He suffered from headaches, ringing in the ear, and painful kidney stones, but refused to take his doctor’s advice to moderate his fondness for food and drink. The death of his daughter Magdalena, in December 1542, further darkened his spirits. In early 1543 he wrote: ‘I can no longer write or read. I feel weak and tired of living. These were painful moments for Luther, suffering from a painful injury in the coronary artery and deep depressions caused by the revival of the papacy, by the attempt of the Jews to reopen the question of the messianism of Jesus of Nazareth and for the new outbreak of the most radical reformist faction, that of the Anabaptists.

But it was precisely for this reason that he could not afford to retire, and he continued his intense activity until his death. He found the strength to publish the famous Wittenberg Reformation in 1545, which was a mild exposition of the new doctrine. A few months later he would react violently to the spread of the rumor of his death, which he attributed to the welches (Italian and French) and denied through his Lies of the welches about the death of Dr. Luther. And in 1545, on the eve of his death, he published one of his most violent pamphlets on the occasion of the conflict that arose at the Council of Trent between the emperor and the pope: On the papacy of Rome founded by the devil. The causticity of such a fierce attack on the papacy acquired even greater prominence thanks to the famous and grotesque caricatures of the pope by Lucas Cranach the Elder to illustrate the publication.

On January 22, 1546, sick and tired, the old reformer made his way to Eisleben, his hometown. He was to act as arbitrator in the dispute between two brothers, Albretcht and Gebhard, Earls of Mansfeld, regarding the income from some mines. The Saxon winter is cold and harsh, and Luther had overestimated his strength. On February 18, at three in the morning, he died almost suddenly. The two doctors who treated him barely had time to do anything and never agreed on the cause of death: a stroke, according to one; pulmonary angina, according to the other; although it could have been anything else as well.

His remains were transferred to Wittenberg in a tin coffin, and the funeral bells sounded as the procession passed. He was buried on February 22 in the church of All Saints, under the pulpit. A year after his death, Emperor Charles V entered the city after the victory over the Protestants at Mühlberg and forced the wife of the Elector of Saxony to give him that square in exchange for the life of her husband taken prisoner. In those circumstances, the Duke of Alba, unfriendly, proposed to the emperor to unearth Luther’s corpse, incinerate it and throw the ashes, but Carlos did not consent to it, arguing that he waged war against the living and not against the dead. It really would have been useless; after his death, the Protestant Reformation It would spread throughout the world by leaps and bounds, penetrating thousands of homes and shaping the way of thinking, feeling and living of millions of beings.