Over the centuries, the image of the Buddha has been depicted so many times that even in the West its effigy is as familiar as any other artistic object. We usually see him sitting on his legs in a meditative attitude, with a more or less prominent protrusion on the cusp of the skull and a hairy mole between the eyebrows, covered by a vaporous priestly mantle and his face haloed by an endearing serenity and sweetness. There is something, however, that sometimes surprises: for an ascetic who has renounced the pleasures of the world and who knows human miseries in-depth, in certain representations he seems excessively well fed and too satisfied.

Buddha in one of his first representations

in the ancient region of Gandhara (1st-2nd centuries)

It is a common belief to consider that the saints led a hermitic life of struggle and sacrifice in search of inner peace, and this was indeed the case in India that Buddha knew, some five hundred years before Jesus Christ. The idea of purification through suffering was common among mature or elderly men, horrified and confused by the wickedness of their contemporaries. Often they abandoned their families and took refuge in the mountains, covered in rags and with a wooden bowl as their only possession, which they used to beg for food. Before becoming the Buddha, which means “the Enlightened One,” Siddharta Gautama also practiced these bodily disciplines selflessly, but it was not long before he found that they were useless.

A prince’s life

Siddharta Gautama was probably born in 558 BC in Kapilavastu, a walled city of the Sakya kingdom located in the southern Himalayan region of India. Also known by the name of Sakyamuni (“the sage of Sakya”), Siddharta was the son of Suddhodana, King of Sakya, and Queen Maya, who came from a powerful family of the kingdom.

According to tradition, Siddharta was born in the Lumbini gardens, when his mother was on her way to visit her own family. Queen Maya died seven days after giving birth and the newborn was raised by her maternal aunt Mahaprajapati. Siddharta grew up surrounded by luxury: he had three palaces, one for winter, one for summer, and a third for the rainy season. In them he enjoyed the presence of numerous maidens, dancers and musicians; he wore silk underwear and a servant accompanied him with a parasol. He is described as a boy with a slender build, very delicate and well educated.

The birth of Buddha

Of his years of study, possibly led by two Brahmins, it is only known that he astonished his teachers by his rapid progress, both in letters and mathematics. Much has been said about the sensitive character of Buddha; but being the son of a king and aspiring to the throne, he must have also been educated in martial arts and in all those disciplines necessary for a monarch. Still, the kingdom of Sakya was hardly a principality of the kingdom of Kosala, on which it depended.

Siddhartha married his cousin Yasodhara when he was around sixteen, according to some sources, or nineteen or perhaps older, according to others. In some legends it is said that he conquered her in a weapons test fighting against various rivals. Nothing is known of this marriage, except that he had a son named Rahula who would become one of his main disciples many years later. The fact of having a male child as a continuator of the dynasty would have made it easier for him to renounce his rights and his consecration to religious life.

Siddhartha’s life was spent most of the time in the royal palace, under parental protection. According to tradition, during his furtive outings to the city, in which he was accompanied by a coachman, the so-called “four encounters” took place. On one occasion, as he was leaving the eastern gate of the palace, he met an old man; on another occasion he went out through the southern gate, he saw a sick man; when he did so through the western gate, he saw a corpse, and another day, as he crossed the northern gate, he met a mendicant religious. Old age, illness, and death indicated the suffering inherent in human life; the religious, the need to find meaning in it. This would lead him to leave behind the walls of the palace in which he had spent most of his life.

The four encounters

At the age of twenty-nine, Siddhartha abandoned his family. He did it at night, mounted on his Kanthaka steed and in the company of his servant Chantaka. His goal was Magadha, a flourishing southern state, where cultural and philosophical changes were taking place. It is possible that he also chose that kingdom, some ten days’ drive from Kapilavastu, to avoid the possibility that his father would demand that he be repatriated. Having traveled part of the way, she cut her hair, stripped off her jewelry and adornments, and handed them over to her servant to return home to her family, with the message that she would not return until she had reached the illumination. The rest of the way he did it as a mendicant, a practice, on the other hand, highly regarded in India at the time. It was also common for men who were mature and philosophically inclined to go into the woods to search for the truth. The unique thing was that he did it at such a young age.

In search of meaning

Once in Rajagaha, the capital of Magadha, the young mendicant caught the attention of the mighty King Bimbisara. The king, accompanied by his entourage, went to visit him at Mount Pandava, where he practiced meditation and asceticism. According to tradition, the monarch offered him as much wealth as he wanted in exchange for agreeing to take command of his battalions of elephants and his elite troops. Siddhartha informed the king of his noble origin and the purpose of his stay in Rajagaha. King Bimbisara did not reiterate the proposal; He only prayed to him to be the first to know the truth achieved if he reached enlightenment.

Siddharta followed the teachings of two yoga teachers, Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputa. The first, followed by three hundred disciples, had reached the stage “where nothing exists”; her hermitage is believed to have been in Vaishi. Siddhartha reached that same stage very early and became convinced of the insufficiency of these teachings to free humanity from its sufferings. Uddaka Ramaputa had six hundred disciples and lived near Rajagaha. His teachings did not satisfy Siddhartha’s cares either.

He then left for Sena, a village along the Nairanjana River, a meeting place for ascetics. These practices were perfectly regulated: they included the control of the mind, the suspension of the breath, the total fast and a very severe diet, all of them painful and painful disciplines. From the stories it is known that Siddhartha was not daunted by his harshness and that, on occasion, those around him believed that he had died. In those days advanced students practiced fasts of up to two months, and nine disciples of Nigantha Nataputta, founder of Jainism, are known to starve to achieve final liberation.

After years of austerities and mortifications that did not bring him enlightenment, Siddharta decided to abandon asceticism, receiving, for the step taken, the criticism of his five companions. To begin with, he bathed in the Nairanjana River to get rid of the dirt that had accumulated in the course of the long process followed. Apparently he was so weak that he could barely get out of the water. He regained his strength thanks to the food offered him by a girl named Sajata. According to various legends, this young woman was the daughter of the chief of the village of Sena; the food he gave the ascetic was a rice soup boiled in milk. A short time later, already restored, Siddharta would reach enlightenment.

The lighting

By all indications, this would have occurred in the city of Gaya, near Sena. Later this city would be called BodhGaya, and a temple would be built in honor of Buddha. Siddhartha spent long hours of meditation in the shade of a sacred fig tree that would later be baptized with the name of Bodhi or “Tree of Enlightenment.” According to the legends, Gautama sat one day under the fig tree and said: “I will not move from here until I know.” The evil god Mara, realizing the gravity and danger of such a challenge, sent him a cascade of temptations, the most important in the form of a trio of lustful odalisques that shook their bellies hysterically at Siddhartha’s bowed head; when he raised his eyes to them, the glare in his gaze turned them into clumsy old women of hideous appearance.

The temptations of Mara

As night fell, he fell into a trance, and the light came to his aid, allowing him to see with radiant clarity the entire intricate chain of causes and effects that regulate life, and the path to salvation and glory. In the so-called first watch of the night he was given the knowledge of his previous existences. In the second he was provided with the third eye or divine vision. At dawn he entered the omniscient knowledge and the entire system of the ten thousand worlds was illuminated. He woke up drunk with knowing.

Siddhartha had understood that human sufferings are intimately linked to the nature of existence, to the fact of being born, and that to escape the wheel of reincarnations it was necessary to overcome ignorance and dispense with passions and desires. Charity was a way of wishing the salvation of all men and of oneself.

In the first moments he had his doubts about whether he should preach the truth that he had reached. His first sermon took place a month later at Sarnath, near Benares, where his five former companions resided. Apparently, they received him very coldly, and Siddhartha rebuked them for their ways of addressing an enlightened person. Eventually, the five formed the initial nucleus of a sect that, given the simplicity of the new message, grew rapidly. Disciple number six was Yasa, the son of a wealthy Benares merchant; Dissatisfied with his sensual and luxurious life, his life had a certain parallel with that of Siddhartha himself. Through Yasa, her entire family was converted.

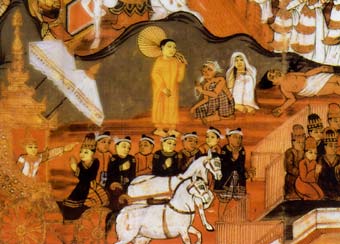

Buddha preaching

When he considered that his disciples were suitably prepared, he sent them to preach the new truth throughout India. They were to go alone, and Siddhartha returned to Uruvela. Among its most important and influential followers was King Bimbisara, who donated a plot of land (the “Bamboo Forest”) to Buddha and his followers to serve as a refuge. However, the disciples spent most of their time begging and preaching, only returning to the farm during the rainy season.

Buddha continued to preach for forty-five years. He visited his hometown several times and toured the Ganges Valley, rising each day at dawn and traveling between fifteen and thirty kilometers a day, generously teaching all men without expecting any reward or distinction. He was not an agitator and was never bothered by the Brahmins, whom he opposed, or by any ruler. The people, attracted by his fame and persuaded of his holiness, came out to greet him, crowded as he passed, and planted his path with flowers.

The Devadatta bombing

One of the conversions that made him most famous was that of his cousin Devadatta, an ambitious man who detested him enough to hatch a plan that would end his life. In cahoots with a few henchmen, and knowing that Buddha would cross a gorge, he stationed himself at the top of it next to a half-detached rock; at the precise moment when Buddha was passing below, the great stone was moved and fell with a crash; Shouts were heard and fears for the life of the teacher were heard, but Buddha emerged unscathed from the dust, with his beatific smile on his lips.

In the last years of his life, Siddhartha suffered severe setbacks. King Bimbisara was dethroned by his own son and the throne of the Sakyas was usurped by Vidudabha, son of King Pasenadi, also the protector of Buddhism. It seems that he was trying to return to his hometown when death befell him. He was eighty-one years old and very weak, but he continued to preach his doctrine until the last moments. From the descriptions made of the infectious disease he contracted, it is believed that the ultimate cause of his death, which occurred in the city of Kusinagara, could have been dysentery. His body was cremated seven days after his death and his ashes were distributed among his followers.

Buddha’s asceticism came from the ancient religions, but it is evident that his purpose was not to reassure his fellow men by introducing them to a new deity or renewing previous rites but to make each one aware of his radical loneliness and teach him to fight against the evils of life. existence. By replacing the liturgies and sacrifices with the contemplation of the world, Buddha gave supreme importance to something very similar to individual and private prayer, valuing meditation above all else, praising meditation and placing the heart of man at the center of the Universe. .

Another reason for his success was undoubtedly his amazing tolerance. There is no Buddhist dogma and therefore no Buddhist is persecuted as a heretic. When looking back, between centuries pregnant with violence and fanaticism, what is most surprising about Buddha is the serene appeal that he makes to reason and the experience of each man: “Do not believe in anything because they teach you the written testimony of a wise old man. Do not believe in anything because it comes from the authority of teachers and priests. Anything that is in accordance with your own experiences and that after arduous investigation manifests itself in accordance with your reason, and leads to your own good and to all living things, accept it as the truth and live accordingly.”